Spencer Lynn is a Senior Scientist with a PhD in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. His research background is in learning, perception, and decision-making using behavioral, neurophysiological, and computational modeling methods. At Charles River, Spencer brings biologically inspired approaches, from neuroscience to behavioral ecology, to the intelligent systems that we build.

Q: What is your favorite part about your job at Charles River Analytics?

A: I came from an academic research background and joined the team at Charles River six-and-a-half years ago. I really like the research vibe here as well as the diversity of projects that I can be part of with a great group of intelligent people. This is my first experience working with software engineers to build products that people get to use, and I really enjoy exploring the applied aspects of my research.

“I’m personally drawn to the richness of the organization and working side by side with people from different backgrounds and fields. Also, did I mention that the people are really great?”

Q: Can you talk a bit more about the interconnection of biology and the natural world, and its influence on technologies?

A: Yes! Here are two examples. First, we can draw on the behavioral ecology of social vertebrates to inform swarm autonomy. For example, it may be useful to enable a robot’s “health” status to affect the risk it will expose itself to, or to have tactical behavior emerge at the level of the swarm in the absence of central control or peer-to-peer negotiation.

Second, we can draw on brain evolution to inform AI and cognitive architectures. The only “general” intelligence we know is human, so we need to deeply examine what concepts like “embodied,” “grounded,” “situated,” and “affordance” mean, from an evolutionary perspective. Five hundred million years of brain evolution calls into question the traditional distinctions among faculties such as perception, categorization, decision, emotion, action, memory, and creativity. These capabilities may not be as modular as we’ve assumed them to be over the history of AI and cognitive science.

For instance, scientists study how humans adapt to changes in the world around them. How do the needs of our bodies dictate the goals that we have, whether those goals are cognitive or physiological? How do these factors construct our response, in the moment, to what’s in our environment? These are all important questions that we try to answer and incorporate in intelligent systems.

“Biology and psychology have a lot to bring to computer science. And the influence goes both ways, computer science and engineering have also had a huge influence on these fields, as well as on neuroscience, for example where hierarchical, generative, causal models show similarity to brain connectivity patterns.”

Q: What motivates you professionally?

A: I’m motivated by the impact my work is making on others. I’m excited to create products that will make a positive impact on those who will ultimately use them. The applied nature of the work means that sometimes we generate ideas or create products that don’t always have an end user. There’s a gap between the prototypes that we build and making the leap into a marketable product. Not all the work we do makes that transition, but it’s exciting when it does!

Previously, I was focused on biology-based research, where you write an article that would likely sit on a shelf someplace. If you’re lucky, it may get cited by someone. It’s important work but beyond basic research, it doesn’t turn into anything that has a larger influence on people.

“I really enjoy the challenge of my job now—trying to create something that will make an impact on the people who will use our products.”

I’m also excited that insights from neuroscience and behavioral ecology can be applied to robotics or other intelligent systems. There are developing theories that I’m really excited to bring into AI.

Examples include how signaling down and up neuronal hierarchies generates and evaluates predictions about the mind, body, and world; how morphology and ecology together produce embodied and grounded cognitive models; and how neuronal architecture and embodied cognition create the flexibility to operate in uncertain or novel situations.

At Charles River I’m able to work with world-class engineers who have the knowledge and expertise to implement these kinds of approaches computationally.

Q: Can you tell us about KWYN™?

A: KWYN stands for “Knows What You Need.” KWYN is a branded platform that encompasses a number of products developed out of Charles Rivers’ decades of research and development in adaptive intelligent training and operations. KWYN assesses and adapts to a learner’s competency to accelerate skill acquisition and retention. In that way, KWYN “knows what you need,” when you need it.

Q: What advice would you give someone new to the field?

A: There is very little information shared in graduate school about the diversity of work opportunities outside of academia. Often, in advanced programs you’re encouraged to aim for a professorship. This is a great path for many students, but I think there needs to be more awareness of alternatives outside of academia.

In the life sciences, for example molecular biology, there’s a more well-known industry base. But in experimental psychology or brain and cognitive sciences, it’s less commonly understood that there is a whole ecosystem of companies like Charles River where you can do novel research in the field that you love and trained in. So, my advice is to look around—there are a lot of different paths available.

Q: Any fun or interesting facts about you that most people do not know?

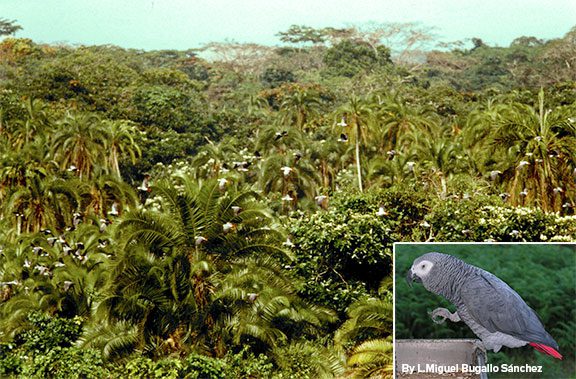

A: At work, people know about my animal research background to some extent, but I think sometimes it still surprises people. My research has included the behavioral ecology of free-ranging whales and dolphins in the Gulf of Mexico and grey parrots in Cameroon, laboratory-based studies of referential communication in dolphins and parrots, and learning in bumblebees.

My postdoctoral work encompassed hospital-based research on psychotic and anxiety disorders, focusing on behavior and neuroscience with patients, and translational research with animal models (mouse, C. elegans, and neuronal cell culture) focusing on behavior, genetics, and cellular signaling.

Outside of work I enjoy spending time with my wife and teenaged daughters. I also like traveling in natural areas, surfing on Cape Cod, and skiing New England.